"Jenny's" letter to "Tracy" from SIG Camp, July 27, 2009.Wild-eyed warnings launched this case in 2008--a preemptive war that became a 4-year fiasco with little regard for the truth, the cost, or the collateral damage.

Most Family Court judges forbid me to write in “their” courtrooms. In Superior Court I once inquired if I could take notes, and the clerk studied me quizzically: Of course! Why not? She even offered me a pen.

But Family Court is a different culture, with a veiled history of unrecorded conversations and backroom secrets. So I do the best I can to copy the public files, to remember what happens in court and to write it down as soon as possible. (I always welcome corrections, documents and other evidence to comprehend these often astonishing cases.)

On Tuesday, the final day of arguments, Judge Debra DiSegna presides, attentive but visibly weary of the mess others left since that first “emergency” ex parte order of April 23rd, 2008.

All week I’ve been trying to reconstruct Tuesday’s arguments and research the legal citations to be sure I understand their significance. Let’s return to that afternoon at Washington County Courthouse.

The stage is set: a lectern poised between the two attorneys. First up to speak, “Barbara’s” lawyer, Cynthia Gifford, reads her long script at the lectern in a trembling voice for the better part of an hour. As far as I can recall, she does not clearly cite state or federal laws, court rules, findings of fact, evidence, or testimony. She beats a single drum, reminding the judge again, again, and again, that a miserable creature sits at the next table.

Her incendiary words fail to ignite any outbursts from “Tracy.” (Folk wisdom prevails: Whenever you point a finger at somebody else, three of your fingers point back at you.) Gifford accuses Tracy of bullying, scheming, invading privacy, harming a child, and having no remorse.

Gifford advises the Court on something she calls “parental competence,” but she offers no evidence of her qualifications. (The opposing attorney later notes that he has raised five children to adulthood. He has 19 grandchildren. But he chooses to focus his remarks on the law.)

Keven McKenna speaks without using the lectern. He stands beside his client, Tracy, and her ADA assistant. He addresses the judge and occasionally turns to acknowledge half a dozen Gifford fans seated beyond Gifford’s partner, Attorney Cherrie Perkins.

The judge must decide this case based only on the law, McKenna says. He refers to “Jenny’s” birth certificate that names her birth mother, Barbara, and her adoptive mother, Tracy, as natural parents with equal rights. He cites the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Santosky v. Kramer (No. 80-5889) (455 U.S. 745 753 1982) that the Fourteenth Amendment protects the fundamental liberty interest of natural parents in the care, custody, and management of their child.

He cites King v. King, 114 A.2d 329 333 A.2d 135 (R.I. 1975) that age-change itself constitutes a significant material change of circumstance sufficient to warrant the trial court to reopen prior orders of custody. He reminds the court that four years is forever in the life of Jenny, who has aged from 11 to 15 while this case dragged on. King also holds that the testimony of a 12-year-old child is highly material.

McKenna notes that Parrillo v. Parrillo, 554 A.2d 1043 (R.I. 1989) assures jurisdiction since “the circumstances and conditions that existed when custody was decided have been changed or altered.”

Gallagher v. Dutton, 895 A.2d 124 (R.I. 2006) shows one parent using a restraining order “as a hammer to justify” not letting the other parent share significantly in the child’s life. As a result, the Supreme Court agreed with the trial justice’s decision “to award sole custody and physical placement” to the parent who had been hammered out of the child’s life.

In Pettinato v. Pettinato, 582 A.2d 913-14 (R.I. 1990) the state Supreme Court established a list of factors that must be weighed in an analysis of the best interest of the child when deciding custody:

1. The wishes of the child’s parent or parents regarding the child’s custody.Jenny’s stated preference from the beginning was to live with Tracy. McKenna notes that two witnesses, both of them parents, one a psychologist, have testified that they do not consider Tracy a danger to Jenny or to other children.

2. The reasonable preference of the child, if the court deems the child to be of sufficient intelligence, understanding, and experience to express a preference.

3. The interaction and interrelationship of the child with the child’s parent or parents, the child’s siblings, and any other person who may significantly affect the child’s best interest.

4. The child’s adjustment to the child’s home, school, and community.

5. The mental and physical health of all individuals involved.

6. The stability of the child’s home environment.

7. The moral fitness of the child’s parents.

8. The willingness and ability of each parent to facilitate a close and continuous parent-child relationship between the child and the other parent.

McKenna avers that Tracy, Barbara and both their homes meet the Pettinato factors--except for the last one:

8. The willingness and ability of each parent to facilitate a close and continuous parent-child relationship between the child and the other parent.Tracy alone meets that one.

Frankly, I distrust this eighth factor, often called the “Friendly Parent” standard. It sounds good in many cases--except where there has been a history of domestic violence, sexual abuse, or coercive control.

In those cases, the “Friendly Parent” standard has too often opened the door for felonious parents to win sole custody of children they terrorize. When the children refuse to visit them, Family Court routinely punishes these youthful attempts at self-protection. The Court has given countless children to abusive parents, who then cut off all normal communication with the parents who tried to protect them.

While I do not believe Barbara is felonious, she and her lawyers have certainly done everything they could to break Jenny and Tracy’s close relationship.

Three years ago, on June 5, 2009, Dr. Judith Lubiner sent an email to both mothers:

I will be writing a letter to Judge Shawcross letting him know that [Jenny’s] stated preference is to live with [Tracy]. . . . I am hopeful that [Jenny] will feel better knowing that someone has expressed her wishes to the judge.Lubiner’s exercise in truth-telling apparently provoked some pushback; ten days later she sent another email:

I regret that I impulsively agreed to do something that, upon consideration, believe was outside the boundaries of my role.A month later, Jenny wrote letters to Lubiner and Barbara from the University of Texas, where Tracy had driven her to attend the Summer Institute for the Gifted (SIG). It was the last summer Barbara would let her attend SIG. The 12-year-old wrote to Tracy:

Dear Mom,Judge DiSegna offers no clue to the decision she will render on May 3rd, at 2 p.m. She informs the parties that she will meet 15-year-old “Jenny” in chambers at 3 p.m. to explain her decision directly to the young woman whose future she is now deciding.

Thank you so much for getting me all the way out to Texas! I know it’s been a hard year for you and you’ve been struggling to pay the bills a lot. I’d like to write this letter . . . to inform you that I am sending the black phone back to [Barbara] because I cannot stand this phone issue any longer . . . .

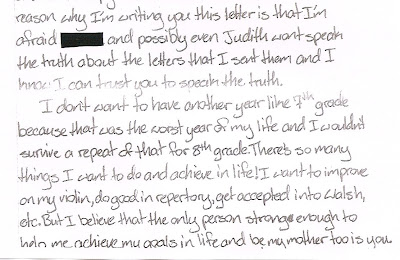

Another reason why I’m writing you this letter is that I’m afraid [Barbara] and possibly even Judith wont speak the truth about the letters that I sent them and I know I can trust you to speak the truth.

I don’t want to have another year like 7th grade because that was the worst year of my life . . . . There’s so many things I want to do and achieve in life! I want to improve on my violin, do good in repertory, get accepted into Walsh, etc. But I believe that the only person strong enough to help me achieve my goals in life and be my mother too is you.