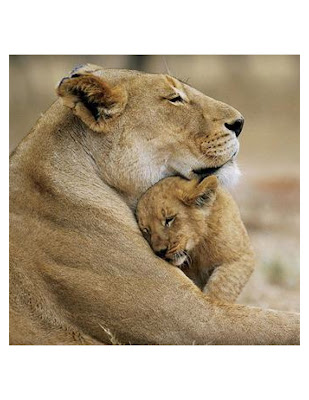

Since we cannot show "Jenny" and her mom, "Tracy," here is a photo they both loved.

On Friday, February 10th, at Rhode Island's Washington County Courthouse, Attorney

Cynthia Gifford asks psychologist Dr.

Ronitte Vilker a jaw-dropping question that goes something like this:

Does Tracy take any responsibility for what has happened here . . . that she has no contact with her daughter?

It is The Remorse Question:

Are you sorry for your crime?

Parole boards routinely ask this of prisoners. Even those falsely accused must express remorse or remain in prison.

But the General Assembly established Family Court as a “civil” court, not a criminal court. Therein lays its recurring failure when civil lawyers fancy themselves prosecutors.

A few weeks ago, Gifford’s partner, Attorney

Cherrie Perkins, whispered to me: "She’s just like a batterer."

Who? I wondered.

Tracy? Gifford? It’s not unusual for batterers to taunt their victims and blame them for abusing the abusers.

This case illustrates the damage being done to children and parents by adversarial litigation in Family Court. The fact that both parents and the attorneys who initiated the case are women removes the frequent distraction of “he-said-she-said” conundrums that prevent people from seeing the systemic failures. Indeed, this one could be a case study for law students in a professional ethics class.

The docket begins on April 24th, 2008. But something mysterious happens the day before which never gets entered on the docket sheet.

Judge

Laureen D’Ambra once told me that she does not allow attorneys to discuss cases with her in chambers. She wants everything on the record. In this case, she even made a note to herself: "based on [representation] of [Attorney] Perkins—Ex parte order is modified--visitation is at the discretion of the Plaintiff."

The day before on April 23rd, 2008, Attorney Gifford presented an "emergency

ex parte order" for Judge D’Ambra's signature that would give her client, “Barbara,” sole custody of 11-year-old “Jenny.” The judge cautiously writes in her own requirements: that this sole custody is "pending a hearing on the motions," that "the current visitation schedule" will continue.

The next day, Gifford apparently returns with Perkins and the revised

ex parte order (with no notice given to Tracy) to clarify that Tracy "shall only have visits with the child in the discretion of the Plaintiff." Judge D'Ambra signs, and her

ex parte order opens the case.

"Ex parte" means that the opposing party is not represented at court. Ironically, these procedures are often intended to help victims of domestic violence.

But batterers' attorneys have learned that the best way to zealously represent a client is to claim there is an "emergency" that requires an

"ex parte order." This gives them a piece of paper with a judge's signature that awards their client sole custody.

The beauty of using Family Court this way is that the judge never meets the victim, while the batterer gets a piece of paper to blanket the community and threaten legal consequences if schools or community programs allow an ostracized parent near their children.

Tracy soon becomes an outcast to everyone who had once welcomed her as an active parent in Jenny's life. These, too, are batterers' tactics: Isolation. Mind games. Psychic damage. They can devastate anyone, especially someone on the autism spectrum, as Tracy is. The baffling process of Family Court gives insiders endless opportunities to bully their opponents.

Tracy testifies that she never met Judge D'Ambra. On September 10, 2008, the next judge,

Raymond Shawcross orders:

. . . the current temporary order awarding sole legal custody of [Jenny] to Plaintiff [Barbara] in no way restricts the rights of either parent from participation as [Jenny's] legal parents in all scheduled health, educational and other outside activities.

Both parents agree to timely provide the other with all pertinent information concerning said activities so as to insure full knowledge by both parents of such activities.

.

Shawcross allows Tracy regular visits and one phone call a day with her daughter, with no text messages. But Jenny has counted on Tracy all her life, and the girl begins sending frequent text messages. Should Tracy ignore her?

Angered by their texting, Barbara seizes the girl’s phone. Tracy gives her another. Eventually, Gifford brings a basketful of cell phones to court that Barbara has confiscated. Eventually the visits are stopped altogether. More on that later.

In 2009 Tracy seeks therapy with Dr. Vilker to cope with the court experience, the trauma, grief, and ambiguous loss.

By 2010, Shawcross says Tracy can send letters to Jenny at summer camp. A few get through. But the camp intercepts the rest and sends them unopened to Gifford, leaving the girl to worry about what could be happening to Tracy.

On that first day, April 23rd, 2008, Gifford presented a “Miscellaneous Complaint” to Judge D’Ambra, a 24-point mixture of truths and fictions. The most resounding truth in the entire document is the last point, which is probably not what Gifford intended to write about the plaintiff, “Barbara,” her client:

24. Plaintiff is fearful that the filing of this matter in the Family Court will cause Plaintiff to become more unstable and take action to further alienate the minor child all to her serious detriment.

That is exactly what happens, and now the attorneys who started it want Tracy to take responsibility for what they themselves have done, as they tried to sever Jenny from all contact with the mom who nurtured her impressive talents.

On that first mysterious day, Gifford also showed Judge D’Ambra a 25-page letter Tracy had written to her estranged partner, Barbara—-Gifford’s client. I find this letter particularly compelling. Despite the extreme wordiness and passion (consistent with Tracy’s high-functioning autism as described by Dr. Vilker) the letter pleads for greater understanding of their daughter:

It is psychologically debilitating to [Jenny] to make her feel like she cannot even come out into the yard or the curbside to see me—-with her face pressed in the window like a prisoner in her own home. (p. 2)

I learn a lot from these family histories, and sometimes see myself reflected in them, for it was my own failures as a mother that makes inspired parents endlessly fascinating to me. I see this in Tracy’s vivid descriptions and in dozens of vibrant photos of her and Jenny engaged with friends, animals, music, crafts, science, sports, and travel.

I recognize myself forty years ago when she describes Barbara coming home from work and walking past the dinner table that Tracy and Jenny had set for three:

[Jenny] said in her little 2-year old precious, innocent way with her arm out stretched eating peas off her plate “come have a seat boodle – we are eating now. . . ,” all happy and oblivious . . . . Your answer was, “Oh, I’m not hungry honey right now—you go ahead and eat.” You ignored me and walked right back into the office to get on email. Again. (p. 4)

Tracy’s frustration sounds like many marriages--indeed like my own husband pleading with me to switch gears and play with our children, not to make them feel like some dreary chore.

She describes Barbara in words that resemble my own behavior when our children were young. I empathize with career-driven parents and wonder if Barbara ever regrets having turned over her life and her child to Gifford and Perkins.

On her first day hearing this case, Judge

Debra DiSegna urges mediation, but Gifford stomps her foot and adamantly shakes her head. For ten minutes at the bench, Gifford's earrings careen back and forth, back and forth. What incentive is there for her to resolve this case?

By 1988, our children were away at college. I worked at a shelter for battered women and discovered the magic of mothers like Tracy. I stood in awe of their parenting skills and watched their children depend on them like lifelines.

Then I saw how often Family Court rips vulnerable children away from proven parents who lack the money to hire lawyers, guardians

ad litem, and psychologists that the Court orders them to hire when abusers fight for custody.

Dr. Vilker’s visceral experience of this Court’s power may give her an important education. Attorney Gifford wants to know if Dr. Vilker reviewed any documents about Tracy in preparing for her testimony.

Yes, says Dr. Vilker.

One, but very briefly.

Do you have it with you? Gifford asks.

Vilker hesitates. Tracy’s attorney objects. Judge DiSegna overrules him.

Yes, says Vilker.

Gifford insists on seeing it.

Vilker demurs, explaining that HIPAA protects the confidentiality of a therapist’s work with a patient.

The Court overrides the law, Judge DiSegna explains. She orders the doctor to produce whatever documents she has.

This is one of the reasons the most respected psychologists, like Dr. Vilker, refuse to do evaluations for Family Court, though it is a coveted market for some.

One psychologist told me that the good he intended to do for his patient was entirely undone when Family Court twisted his words to imply exactly the opposite of what was true.

We need good therapists like Dr. Vilker to help the Court understand symptoms like Tracy’s, and also to help their colleagues confront the damage Family Court is doing to the integrity of their profession.

At one point Judge DiSegna says it might surprise Dr. Vilker to know Jenny had “confessed” that Tracy had ordered her to fail at school. Dr. Vilker says she would need more information to comment.

I suspect Dr. Vilker might have another perspective on whatever it is that Jenny actually said. But the judge sealed that document and seems to be taunting Tracy by leaking a tiny portion of it in court while withholding the rest.

Judge Shawcross did the same last time Jenny endured a grilling by lawyers in chambers only to have nothing come from it: No contact with the parent she openly longs for.

Shawcross, too, sealed her testimony, but revealed a small part, saying Jenny felt

guilty—as if she were the one who caused the chaos that began in this room on April 23rd, 2008.

The irony is that Jenny and Tracy were not even here the day it started. Yet they are the ones being treated as criminals for nearly four years. And Jenny, like many children whose lives are decimated by Family Court, believes she is responsible for the persecution of this cherished parent, whom she knows to be especially vulnerable.

Does it satisfy Attorney Gifford, who started it all, to know that Jenny feels responsible?

When Dr. Vilker returns to court this Wednesday, will Gifford press to see how much confidential information she can extract from the therapist? Will she continue to intrude on Dr. Vilker’s schedule, to run up her own billable hours and run down the clock so Jenny can no longer choose her high school?

This is another common Family Court tactic for batterers—-to punish any witness who steps forward, to break down the victim’s support system, and to compound the cost for everyone.

This week I plan to write at

http://CustodyScam.blogspot.com about the cabals of court.

Then I’ll describe the cabal that lived off this case and how it ended all communication between Jenny and her lifeline mom, as Gifford predicted it would, by taking

action to further alienate the minor child--all to her serious detriment.

Here's the first letter "Tracy" sent "Jenny" at camp in 2010 before her letters were intercepted and sent to Gifford and Perkins.

(Enlarge it with a single click.)