Tracy’s attorney, Keven McKenna, objected repeatedly, questioning the need for such a barrage of insinuation that appeared calculated to trigger Tracy’s symptoms of high-functioning autism. Judge DiSegna overruled McKenna and demanded answers.

Tracy’s ADA aide was not allowed to sit beside her, where she could have touched Tracy’s arm or leg to focus her back on her body in the way that helps those with neurological disorders. McKenna and the aide searched for the magnets Tracy uses to calm herself and settled for coins she could shift in her palms.

Two days later, at the Family Court’s statewide training on the neurological and psychological impact of childhood trauma, the keynote speakers cogently described what was happening to Tracy in DiSegna’s courtroom. (I’ve posted more on this conference at CustodyScam.blogspot.com)

Licensed clinical social worker Robert Hagberg and Dr. James Greer described how “rockers” need physical movement to “quell their overactive limbic systems” as a normal and necessary balancing function of the brain’s cerebellar vermis. When teachers (or judges) think words should be sufficient to stop this behavior, they are simply mistaken.

Tracy and her brother were both born with autism, which may have contributed to later traumatic episodes. She was four when a playmate teased her by pulling away a pillow as she jumped. Her crash onto cinder blocks split open her skull. At nine she tried to pet a dog who bit away part of her face. Repeated surgeries gradually rebuilt her face and skull until she was twenty, when she said she could not endure any more reconstructive procedures.

She went on to serve in the U.S. Air Force with top clearance until she left in fear of the “don’t-ask-don’t-tell” strictures on gay and lesbian service members. An Air Force friend agreed to father a child for her and her partner, Barbara, who gave birth to Jenny in 1996. Tracy adopted Jenny. The girl’s birth certificate includes both mothers’ names as her legal parents.

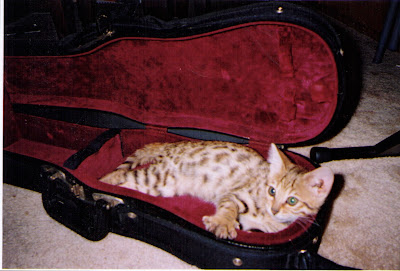

Barbara’s attorneys, Cynthia Gifford and Cherrie Perkins, now appear intent on triggering Tracy’s symptoms as if to imply she is an unfit parent. Scores of photographs since Jenny’s birth--full of exuberant activities, trips, pets, and friends--convey the unmistakable bond between Jenny and Tracy, whose disability has never hindered her from being an inspired and nurturing mother.

Last week, Tracy testified that throughout 2008, she never even met Judge Laureen D’Ambra, who signed the emergency ex parte order that gave temporary sole custody to Barbara. In 2010, Dr. Robin Stern, M.D., Chief of Psychiatry at Kent County Hospital, testified that Tracy was not mentally ill. She wrote:

[Tracy] has no signs of psychosis, delirium, severe depression, panic disorder or substance abuse. Her presentation is consistent with what is called High Functioning Autism. A person with this disorder can present as paranoid, especially under conditions of increased anxiety and stress. They can look more disturbed than is actually the case. They are frequently misunderstood by someone unaware of autistic behavior as they have difficulty picking up appropriate social cues.Judge Raymond Shawcross disregarded Dr. Stern's expertise in 2011 when he ruled that Tracy was mentally ill. The history of this case illustrates how cabals, rife with rumors and false insinuations, influence far-reaching judicial decisions—a subject for another post.

In terms of how her behavior would impact on a child, I do not see any dangerous or concerning impulses, thoughts or activity. Children are much more adaptable in the setting of unusual behavior and a daughter who is accustomed to a mother with autism would not be alarmed or confused. I would be more worried about the impact of loss on a child whose mother has been taken away.

Tonight, I am most concerned about Jenny, who is still forbidden to communicate in any way with Tracy. Tomorrow, Barbara will bring their daughter, now 15, to answer questions from the lawyers and Judge DiSegna. Will they grill her in the same taunting, abusive way? Or will they hear what she needs to say?

Last Wednesday, Attorney Gifford tried to condemn Tracy for bringing Jenny into the courthouse to observe public hearings in 2009.

Tracy had picked up Jenny when snow closed her school. But there were still plenty of opportunities for learning. And Jenny had pressing questions that needed answers. What better way for a conscientious parent to teach a smart youth about the forum where these decisions are getting made than to take her into an American courtroom and watch? Predictably, Judge Shawcross exploded and ordered them out of his court.

But the court file still holds Jenny's handwritten affidavit in green ink:

I cannot take living like this anymore, because it is driving me crazy. I am depressed and angry because of this whole custody battle . . . . I don't know how the whole court thing works, but I know somewhere, someone has said something inaccurate or I could be with [Tracy] right now. . . . . There is sooo much more to tell you about my situation and what I want. May I please talk to you?

On Wednesday, Attorney Gifford accused Tracy of trying to tell Jenny what her rights are under the law that allows 14-year-olds to go to Probate Court for a guardian ad litem of their own choosing.

Last Friday, Chief Judge Bedrosian’s statewide training introduced a panel of youth who had lived in the foster care system. They compellingly asserted their precept: “Nothing about us without us.”

Whenever I research custody cases, it is an important principle for me to try to detect the children's concerns. The last time Jenny spoke to me in private, she despondently told me that no one assigned by the court was listening to her. She deserves the opportunity to speak fully, without any harassment from lawyers, about her needs and hopes for the future.

In addition to ADA accommodations, the Family Court needs to accommodate this basic principle: Nothing should be ordered for Jenny without respecting her voice in the process.